How to win at interviews

Thursday, August 28th, 2014Biz Stone on how he faked it and Google hired him. One genius moment of believing you’re who you could be. And now he is.

Biz Stone on how he faked it and Google hired him. One genius moment of believing you’re who you could be. And now he is.

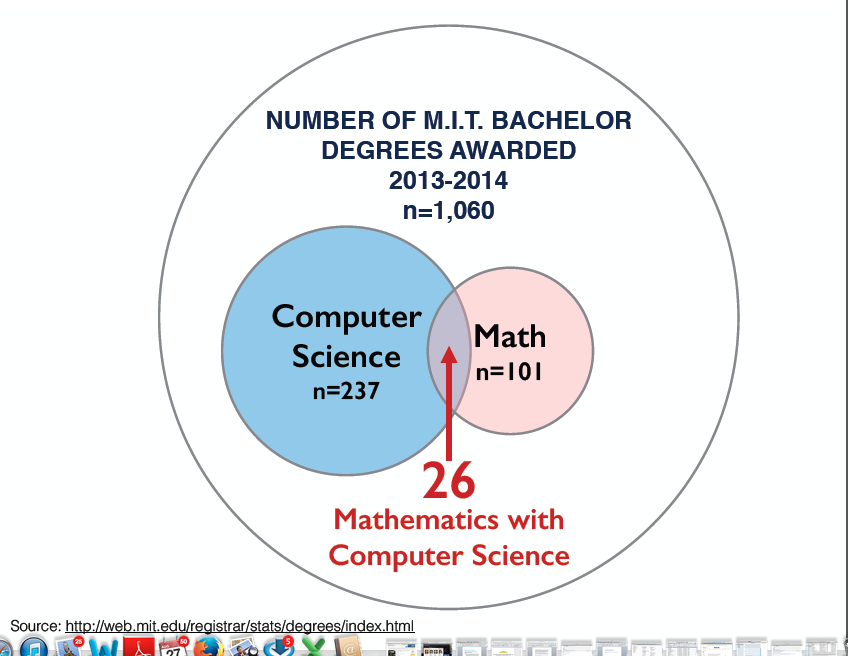

I interviewed Michael Rappa, the North Carolina State University computer science professor who created the first master’s in analytics program, back in 2007. He’s got more experience training data scientists than anybody else in academia, so I asked him whether companies have realistic expectations for the data scientists they hire. He said companies want data scientists to be strong at both programming and mathematics.

Almost nobody has this background. Rappa shared with me a slide he put together showing the number of MIT undergraduates who graduated with a degree in what’s called 18C, mathematics with computer science. The numbers are tiny, certainly far less than one would hope. This is MIT, an intensely technical place. The chart also reflects a big year for 18C. See for yourself:

I interviewed Amy-Jill Levine in advance of the release of her new book, Short Stories by Jesus. She’s funny and enormously knowledgeable at the same time, and the book is like that, too. Never did I expect to find myself thinking about how Rocky and Bullwinkle are like the parables. I have this quote I’m not likely to use in the Q&A. It doesn’t fit. But I liked it. It said something true about leaps of faith.

I interviewed Amy-Jill Levine in advance of the release of her new book, Short Stories by Jesus. She’s funny and enormously knowledgeable at the same time, and the book is like that, too. Never did I expect to find myself thinking about how Rocky and Bullwinkle are like the parables. I have this quote I’m not likely to use in the Q&A. It doesn’t fit. But I liked it. It said something true about leaps of faith.

“I’m frequently asked, since you know so much about Jesus and since you so appreciate his teachings, why don’t you worship him? But belief, faith, I don’t think have anything to do with academics or how smart you are. Belief is not like sudoku, that if you’re smart enough you can all get the right answers. Belief is more like love. What makes perfect sense to one person makes absolutely no sense to someone else.”

We know the world isn’t flat, but spiky. Whether we can do things about those spikes drives U.S. domestic political debates. Do we want a society tilted towards conserving resources for those who already have them, or are we stronger if we shift resources towards liberating people from circumstances they didn’t create, but weigh them down? Can we smooth the frictions created by things like where we’re born and in what circumstances? At its core, US domestic politics is about whether helping others really helps.

One of the most difficult questions in this fundamental debate involves whether spreading resources can be made to work broadly. We know that it betters our society as a whole to pool resources for public education. Even though public education is terribly uneven, ensuring the vast majority of Americans can read, write and do math is good for our overall society. We know it betters our society to share resources to make sure there is clean water. Clean water improves everyone’s health and life expectancy, creating a more stable society. But what about sharing resources to actually lift people out of poverty?

Farah Stockman, the talented Boston Globe columnist who is also a friend, volunteered years ago in a summer camp for kids from public housing. She went back two decades later to see whether the camp she worked in had made a difference. What she found in this series of six articles was complicated. The ones who made it out seem so focused and disciplined that they might have done it anyway, though it’s clear that they benefited from the networking opportunity found in a camp that connected them with outstanding Harvard undergraduates. The ones who don’t get out show how our public policy system actually can encourage single motherhood, even for people with talent and some drive.One intriguing individual seems to succeed in her own way, but she avoids Stockman and so we’re not really sure what worked. I hope Farah’s well-deserved Pulliam Fellowship means she can continue to explore the questions she raises in this excellent series.

Don’t have time to read all six pieces? The New York Times summarized them here.